扩充提供的 Thread

system,优化线程同步问题。

Requirement

In this assignment, we give you a minimally functional thread system. Your job

is to extend the functionality of this system to gain a better understanding

of synchronization problems.

You will be working primarily in the threads directory for this assignment,

with some work in the devices directory on the side. Compilation should be

done in the threads directory.

Before you read the description of this project, you should read all of the

following sections: 1. Introduction, C. Coding Standards, E. Debugging Tools,

and F. Development Tools. You should at least skim the material from A.1

Loading through A.5 Memory Allocation, especially A.3 Synchronization. To

complete this project you will also need to read B. 4.4BSD Scheduler.

Background

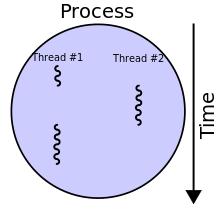

Understanding Threads

The first step is to read and understand the code for the initial thread

system. Pintos already implements thread creation and thread completion, a

simple scheduler to switch between threads, and synchronization primitives

(semaphores, locks, condition variables, and optimization barriers).

Some of this code might seem slightly mysterious. If you haven’t already

compiled and run the base system, as described in the introduction (see

section 1. Introduction), you should do so now. You can read through parts of

the source code to see what’s going on. If you like, you can add calls to

printf() almost anywhere, then recompile and run to see what happens and in

what order. You can also run the kernel in a debugger and set breakpoints at

interesting spots, single-step through code and examine data, and so on.

When a thread is created, you are creating a new context to be scheduled. You

provide a function to be run in this context as an argument to

thread_create(). The first time the thread is scheduled and runs, it starts

from the beginning of that function and executes in that context. When the

function returns, the thread terminates. Each thread, therefore, acts like a

mini-program running inside Pintos, with the function passed to

thread_create() acting like main().

At any given time, exactly one thread runs and the rest, if any, become

inactive. The scheduler decides which thread to run next. (If no thread is

ready to run at any given time, then the special “idle” thread, implemented in

idle(), runs.) Synchronization primitives can force context switches when one

thread needs to wait for another thread to do something.

The mechanics of a context switch are in threads/switch.S, which is 80x86

assembly code. (You don’t have to understand it.) It saves the state of the

currently running thread and restores the state of the thread we’re switching

to.

Using the GDB debugger, slowly trace through a context switch to see what

happens (see section E.5 GDB). You can set a breakpoint on schedule() to start

out, and then single-step from there.(1) Be sure to keep track of each

thread’s address and state, and what procedures are on the call stack for each

thread. You will notice that when one thread calls switch_threads(), another

thread starts running, and the first thing the new thread does is to return

from switch_threads(). You will understand the thread system once you

understand why and how the switch_threads() that gets called is different from

the switch_threads() that returns. See section A.2.3 Thread Switching, for

more information.

Warning!

In Pintos, each thread is assigned a small, fixed-size execution stack just

under 4 kB in size. The kernel tries to detect stack overflow, but it cannot

do so perfectly. You may cause bizarre problems, such as mysterious kernel

panics, if you declare large data structures as non-static local variables,

e.g. int buf[1000];. Alternatives to stack allocation include the page

allocator and the block allocator (see section A.5 Memory Allocation).

Source Files

Refer to link for a brief overview of the files in the threads directory. You

will not need to modify most of this code, but the hope is that presenting

this overview will give you a start on what code to look at.

Synchronization

Proper synchronization is an important part of the solutions to these

problems. Any synchronization problem can be easily solved by turning

interrupts off: while interrupts are off, there is no concurrency, so there’s

no possibility for race conditions. Therefore, it’s tempting to solve all

synchronization problems this way, but don’t. Instead, use semaphores, locks,

and condition variables to solve the bulk of your synchronization problems.

Read the tour section on synchronization (see section A.3 Synchronization) or

the comments in threads/synch.c if you’re unsure what synchronization

primitives may be used in what situations.

In the Pintos projects, the only class of problem best solved by disabling

interrupts is coordinating data shared between a kernel thread and an

interrupt handler. Because interrupt handlers can’t sleep, they can’t acquire

locks. This means that data shared between kernel threads and an interrupt

handler must be protected within a kernel thread by turning off interrupts.

This project only requires accessing a little bit of thread state from

interrupt handlers. For the alarm clock, the timer interrupt needs to wake up

sleeping threads. In the advanced scheduler, the timer interrupt needs to

access a few global and per-thread variables. When you access these variables

from kernel threads, you will need to disable interrupts to prevent the timer

interrupt from interfering.

When you do turn off interrupts, take care to do so for the least amount of

code possible, or you can end up losing important things such as timer ticks

or input events. Turning off interrupts also increases the interrupt handling

latency, which can make a machine feel sluggish if taken too far.

The synchronization primitives themselves in synch.c are implemented by

disabling interrupts. You may need to increase the amount of code that runs

with interrupts disabled here, but you should still try to keep it to a

minimum.

Disabling interrupts can be useful for debugging, if you want to make sure

that a section of code is not interrupted. You should remove debugging code

before turning in your project. (Don’t just comment it out, because that can

make the code difficult to read.)

There should be no busy waiting in your submission. A tight loop that calls

thread_yield() is one form of busy waiting.

Development Suggestions

In the past, many groups divided the assignment into pieces, then each group

member worked on his or her piece until just before the deadline, at which

time the group reconvened to combine their code and submit. This is a bad

idea. We do not recommend this approach. Groups that do this often find that

two changes conflict with each other, requiring lots of last-minute debugging.

Some groups who have done this have turned in code that did not even compile

or boot, much less pass any tests.

Instead, we recommend integrating your team’s changes early and often, using a

source code control system such as Git (see section F.3 Git). This is less

likely to produce surprises, because everyone can see everyone else’s code as

it is written, instead of just when it is finished. These systems also make it

possible to review changes and, when a change introduces a bug, drop back to

working versions of code.

You should expect to run into bugs that you simply don’t understand while

working on this project. When you do, reread the appendix on debugging tools,

which is filled with useful debugging tips that should help you to get back up

to speed (see section E. Debugging Tools). Be sure to read the section on

backtraces (see section E.4 Backtraces), which will help you to get the most

out of every kernel panic or assertion failure.

Requirements

Design Document

Before you turn in your project, you must copy the project 1 design document

template into your source tree under the name pintos/src/threads/DESIGNDOC and

fill it in. We recommend that you read the design document template before you

start working on the project. See section D. Project Documentation, for a

sample design document that goes along with a fictitious project.

Alarm Clock

Exercise 1.1

Reimplement timer_sleep(), defined in devices/timer.c. Although a working

implementation is provided, it “busy waits,” that is, it spins in a loop

checking the current time and calling thread_yield() until enough time has

gone by. Reimplement it to avoid busy waiting.

- Function: void timer_sleep (int64_t ticks)

Suspends execution of the calling thread until time has advanced by at least x

timer ticks. Unless the system is otherwise idle, the thread need not wake up

after exactly x ticks. Just put it on the ready queue after they have waited

for the right amount of time. timer_sleep() is useful for threads that operate

in real-time, e.g. for blinking the cursor once per second.

The argument to timer_sleep() is expressed in timer ticks, not in milliseconds

or any another unit. There are TIMER_FREQ timer ticks per second, where

TIMER_FREQ is a macro defined in devices/timer.h. The default value is 100. We

don’t recommend changing this value, because any change is likely to cause

many of the tests to fail.

Separate functions timer_msleep(), timer_usleep(), and timer_nsleep() do exist

for sleeping a specific number of milliseconds, microseconds, or nanoseconds,

respectively, but these will call timer_sleep() automatically when necessary.

You do not need to modify them.

If your delays seem too short or too long, reread the explanation of the -r

option to pintos (see section 1.1.4 Debugging versus Testing).

The alarm clock implementation is not needed for later projects, although it

could be useful for project 4.

Priority Scheduling

Exercise 1.2.1

Implement priority scheduling in Pintos. When a thread is added to the ready

list that has a higher priority than the currently running thread, the current

thread should immediately yield the processor to the new thread. Similarly,

when threads are waiting for a lock, semaphore, or condition variable, the

highest priority waiting thread should be awakened first. A thread may raise

or lower its own priority at any time, but lowering its priority such that it

no longer has the highest priority must cause it to immediately yield the CPU.

Thread priorities range from PRI_MIN (0) to PRI_MAX (63). Lower numbers

correspond to lower priorities, so that priority 0 is the lowest priority and

priority 63 is the highest. The initial thread priority is passed as an

argument to thread_create(). If there’s no reason to choose another priority,

use PRI_DEFAULT (31). The PRI_ macros are defined in threads/thread.h, and you

should not change their values.

One issue with priority scheduling is “priority inversion”. Consider high,

medium, and low priority threads H, M, and L, respectively. If H needs to wait

for L (for instance, for a lock held by L), and M is on the ready list, then H

will never get the CPU because the low priority thread will not get any CPU

time. A partial fix for this problem is for H to “donate” its priority to L

while L is holding the lock, then recall the donation once L releases (and

thus H acquires) the lock.

Exercise 1.2.2

Implement priority donation. You will need to account for all different

situations in which priority donation is required.

Be sure to handle multiple donations, in which multiple priorities are donated

to a single thread. You must also handle nested donation: if H is waiting on a

lock that M holds and M is waiting on a lock that L holds, then both M and L

should be boosted to H’s priority. If necessary, you may impose a reasonable

limit on depth of nested priority donation, such as 8 levels.

You must implement priority donation for locks. You need not implement

priority donation for the other Pintos synchronization constructs. You do need

to implement priority scheduling in all cases.

Exercise 1.2.3

Finally, implement the following functions that allow a thread to examine and

modify its own priority. Skeletons for these functions are provided in

threads/thread.c.

- Function: void thread_set_priority (int new_priority)

Sets the current thread’s priority to new_priority. If the current thread no

longer has the highest priority, yields. - Function: int thread_get_priority (void)

Returns the current thread’s priority. In the presence of priority donation,

returns the higher (donated) priority.

You need not provide any interface to allow a thread to directly modify other

threads’ priorities.

The priority scheduler is not used in any later project.

Advanced Scheduler

Exercise 1.3

Implement a multilevel feedback queue scheduler similar to the 4.4BSD

scheduler to reduce the average response time for running jobs on your system.

See section B. 4.4BSD Scheduler, for detailed requirements.

Like the priority scheduler, the advanced scheduler chooses the thread to run

based on priorities. However, the advanced scheduler does not do priority

donation. Thus, we recommend that you have the priority scheduler working,

except possibly for priority donation, before you start work on the advanced

scheduler.

You must write your code to allow us to choose a scheduling algorithm policy

at Pintos startup time. By default, the priority scheduler must be active, but

we must be able to choose the 4.4BSD scheduler with the -mlfqs kernel option.

Passing this option sets thread_mlfqs, declared in threads/thread.h, to true

when the options are parsed by parse_options(), which happens early in main().

When the 4.4BSD scheduler is enabled, threads no longer directly control their

own priorities. The priority argument to thread_create() should be ignored, as

well as any calls to thread_set_priority(), and thread_get_priority() should

return the thread’s current priority as set by the scheduler.

The advanced scheduler is not used in any later project.

FAQ

How much code will I need to write?

Here’s a summary of our reference solution, produced by the diffstat program.

The final row gives total lines inserted and deleted; a changed line counts as

both an insertion and a deletion.

The reference solution represents just one possible solution. Many other

solutions are also possible and many of those differ greatly from the

reference solution. Some excellent solutions may not modify all the files

modified by the reference solution, and some may modify files not modified by

the reference solution.

devices/timer.c. | 42 +++++-

threads/fixed-point.h | 120 ++++++++++++++++++

threads/synch.c | 88 ++++++++++++-

threads/thread.c. | 196 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++—-

threads/thread.h. | 23 +++

5 files changed, 440 insertions(+), 29 deletions(-)

fixed-point.h is a new file added by the reference solution.

How do I update the Makefiles when I add a new source file?

To add a .c file, edit the top-level Makefile.build. Add the new file to

variable dir_SRC, where dir is the directory where you added the file. For

this project, that means you should add it to threads_SRC or devices_SRC. Then

run make. If your new file doesn’t get compiled, run make clean and then try

again.

When you modify the top-level Makefile.build and re-run make, the modified

version should be automatically copied to threads/build/Makefile. The converse

is not true, so any changes will be lost the next time you run make clean from

the threads directory. Unless your changes are truly temporary, you should

prefer to edit Makefile.build.

A new .h file does not require editing the Makefiles.

What does warning: no previous prototype for `func’ mean?

It means that you defined a non-static function without preceding it by a

prototype. Because non-static functions are intended for use by other .c

files, for safety they should be prototyped in a header file included before

their definition. To fix the problem, add a prototype in a header file that

you include, or, if the function isn’t actually used by other .c files, make

it static.

What is the interval between timer interrupts?

Timer interrupts occur TIMER_FREQ times per second. You can adjust this value

by editing devices/timer.h. The default is 100 Hz.

We don’t recommend changing this value, because any changes are likely to

cause many of the tests to fail.

How long is a time slice?

There are TIME_SLICE ticks per time slice. This macro is declared in

threads/thread.c. The default is 4 ticks.

We don’t recommend changing this value, because any changes are likely to

cause many of the tests to fail.

How do I run the tests?

See section 1.2.1 Testing.

Why do I get a test failure in pass()?

You are probably looking at a backtrace that looks something like this:

0xc0108810: debug_panic (lib/kernel/debug.c:32)

0xc010a99f: pass (tests/threads/tests.c:93)

0xc010bdd3: test_mlfqs_load_1 (…threads/mlfqs-load-1.c:33)

0xc010a8cf: run_test (tests/threads/tests.c:51)

0xc0100452: run_task (threads/init.c:283)

0xc0100536: run_actions (threads/init.c:333)

0xc01000bb: main (threads/init.c:137)

This is just confusing output from the backtrace program. It does not actually

mean that pass() called debug_panic(). In fact, fail() called debug_panic()

(via the PANIC() macro). GCC knows that debug_panic() does not return, because

it is declared NO_RETURN (see section E.3 Function and Parameter Attributes),

so it doesn’t include any code in fail() to take control when debug_panic()

returns. This means that the return address on the stack looks like it is at

the beginning of the function that happens to follow fail() in memory, which

in this case happens to be pass().

See section E.4 Backtraces, for more information.

How do interrupts get re-enabled in the new thread following schedule()?

Every path into schedule() disables interrupts. They eventually get re-enabled

by the next thread to be scheduled. Consider the possibilities: the new thread

is running in switch_thread() (but see below), which is called by schedule(),

which is called by one of a few possible functions:

- thread_exit(), but we’ll never switch back into such a thread, so it’s uninteresting.

- thread_yield(), which immediately restores the interrupt level upon return from schedule().

- thread_block(), which is called from multiple places:

- sema_down(), which restores the interrupt level before returning.

- idle(), which enables interrupts with an explicit assembly STI instruction.

- wait() in devices/intq.c, whose callers are responsible for re-enabling interrupts.

There is a special case when a newly created thread runs for the first time.

Such a thread calls intr_enable() as the first action in kernel_thread(),

which is at the bottom of the call stack for every kernel thread but the

first.

Alarm Clock FAQ

Do I need to account for timer values overflowing?

Don’t worry about the possibility of timer values overflowing. Timer values

are expressed as signed 64-bit numbers, which at 100 ticks per second should

be good for almost 2,924,712,087 years. By then, we expect Pintos to have been

phased out of the Computer Science curriculum.

Priority Scheduling FAQ

Doesn’t priority scheduling lead to starvation?

Yes, strict priority scheduling can lead to starvation because a thread will

not run if any higher-priority thread is runnable. The advanced scheduler

introduces a mechanism for dynamically changing thread priorities.

Strict priority scheduling is valuable in real-time systems because it offers

the programmer more control over which jobs get processing time. High

priorities are generally reserved for time-critical tasks. It’s not “fair,”

but it addresses other concerns not applicable to a general-purpose operating

system.

What thread should run after a lock has been released?

When a lock is released, the highest priority thread waiting for that lock

should be unblocked and put on the list of ready threads. The scheduler should

then run the highest priority thread on the ready list.

If the highest-priority thread yields, does it continue running?

Yes. If there is a single highest-priority thread, it continues running until

it blocks or finishes, even if it calls thread_yield(). If multiple threads

have the same highest priority, thread_yield() should switch among them in

“round robin” order.

What happens to the priority of a donating thread?

Priority donation only changes the priority of the donee thread. The donor

thread’s priority is unchanged. Priority donation is not additive: if thread A

(with priority 5) donates to thread B (with priority 3), then B’s new priority

is 5, not 8.

Can a thread’s priority change while it is on the ready queue?

Yes. Consider a ready, low-priority thread L that holds a lock. High-priority

thread H attempts to acquire the lock and blocks, thereby donating its

priority to ready thread L.

Can a thread’s priority change while it is blocked?

Yes. While a thread that has acquired lock L is blocked for any reason, its

priority can increase by priority donation if a higher-priority thread

attempts to acquire L. This case is checked by the priority-donate-sema test.

Can a thread added to the ready list preempt the processor?

Yes. If a thread added to the ready list has higher priority than the running

thread, the correct behavior is to immediately yield the processor. It is not

acceptable to wait for the next timer interrupt. The highest priority thread

should run as soon as it is runnable, preempting whatever thread is currently

running.

How does thread_set_priority() affect a thread receiving donations?

It sets the thread’s base priority. The thread’s effective priority becomes

the higher of the newly set priority or the highest donated priority. When the

donations are released, the thread’s priority becomes the one set through the

function call. This behavior is checked by the priority-donate-lower test.

Doubled test names in output make them fail.

Suppose you are seeing output in which some test names are doubled, like this:

(alarm-priority) begin

(alarm-priority) (alarm-priority) Thread priority 30 woke up.

Thread priority 29 woke up.

(alarm-priority) Thread priority 28 woke up.

What is happening is that output from two threads is being interleaved. That

is, one thread is printing “(alarm-priority) Thread priority 29 woke up.\n”

and another thread is printing “(alarm-priority) Thread priority 30 woke

up.\n”, but the first thread is being preempted by the second in the middle of

its output.

This problem indicates a bug in your priority scheduler. After all, a thread

with priority 29 should not be able to run while a thread with priority 30 has

work to do.

Normally, the implementation of the printf() function in the Pintos kernel

attempts to prevent such interleaved output by acquiring a console lock during

the duration of the printf call and releasing it afterwards. However, the

output of the test name, e.g., (alarm-priority), and the message following it

is output using two calls to printf, resulting in the console lock being

acquired and released twice.

Advanced Scheduler FAQ

How does priority donation interact with the advanced scheduler?

It doesn’t have to. We won’t test priority donation and the advanced scheduler

at the same time.

Can I use one queue instead of 64 queues?

Yes. In general, your implementation may differ from the description, as long

as its behavior is the same.

Some scheduler tests fail and I don’t understand why. Help!

If your implementation mysteriously fails some of the advanced scheduler

tests, try the following:

- Read the source files for the tests that you’re failing, to make sure that you understand what’s going on. Each one has a comment at the top that explains its purpose and expected results.

- Double-check your fixed-point arithmetic routines and your use of them in the scheduler routines.

- Consider how much work your implementation does in the timer interrupt. If the timer interrupt handler takes too long, then it will take away most of a timer tick from the thread that the timer interrupt preempted. When it returns control to that thread, it therefore won’t get to do much work before the next timer interrupt arrives. That thread will therefore get blamed for a lot more CPU time than it actually got a chance to use. This raises the interrupted thread’s recent CPU count, thereby lowering its priority. It can cause scheduling decisions to change. It also raises the load average